The Chubb Archive is part of The History of Locks Museum Resources

Contact our curator for more information

© 2004 - 2016

Your one-stop resource for dating & information on vintage and antique Chubb Locks, Safes & Security Equipment

Export is Fun

Mr. D.R.E. Ibbs’ personal memories of his 41 years with Chubb

Introduction

I was just 17 and already my dreams of a career lay in ruins; I had just failed my preliminary medical examination for Sandhurst. I had long dreamed of seeing the world, an unlikely ambition for a young man from a working-class home in the 1950s. My father had been a regular soldier for a time after the First World War and his stories coupled with those of an enthusiastic military careers teacher, Major ‘Mousey’ Holmes, at the grammar school I attended, had fired my imagination of how far I could go.

My father suggested an alternative career in the police, but two further failed medicals only confirmed that I was slightly short-sighted. The remainder of my school career in the lower sixth form passed without any great effort or enthusiasm on my part and by the end of the summer term, July 1950, I still had no idea of what career I should follow. Fortunately for me, Wolverhampton boasted a very good juvenile employment bureau at that time and every school leaver was interviewed by a bureau member before the end of term. As the premier school in Wolverhampton, the bureau manager Mr Cartledge, carried out our interviews himself. He asked what I planned to do, work or further education and made no comment to my reply of “No idea”, and my explanation why this was so, except to make a further appointment for me to see him in August.

At this interview, he listened very carefully to my distress story of medical failures and pressed me to explain why I had opted for a career as a regular Army officer. Finally, when I stated that I had a great ambition to see as much of the world as possible, he smiled and advised he might have just the job for me. So it was later that month, I attended the Chubb’s Wednesfield Road offices and was interviewed by Leslie Tinkler and Leonard Dunham. After a lengthy discussion with Mr Dunham regarding my educational qualifications, ambitions and hobbies, he offered me prospective employment as a student engineering apprentice with a view to joining the company's export department, subject to my training being completed in a satisfactory manner and my ambitions remaining unchanged. So it was that on the fourth of September 1950, I joined Chubb Lock and Safe Company as a Student Apprentice.

Apprenticeship

The transition from the sheltered life of an all boys Grammar School, to the rough and tumble of an engineering factory was a rude shock. In the 1950s, the company did not have an apprentice school, and on joining, all apprentices started in the tool room, in order to familiarise themselves with hand tools and measuring instruments. I was placed with a very pleasant gentleman, who was a good toolmaker although unfortunately, he had very little idea of how to instruct apprentices. After two or three weeks, when I learned and did very little, the charge hand in the tool room, spotted the dilemma and placed me with the model maker, whose name was Albert Ling. He was an elderly gentleman who had served in the First World War as a cavalryman and was all that I could ask for in the way of a patient instructor. In addition to teaching me the basic engineering skills in the use of hand tools, I was extremely fortunate in that during the period of time with him, he made several prototypes or models, which gave me an excellent insight into the problems of developing new products.

During the next period of six months instruction in the tool room, I was expected to do all the tasks given to the trade apprentices; this included amongst other things, collecting the tea for the tool makers from the canteen, washing the mugs and generally making oneself useful. The other apprentices had a very smart trick for enhancing their very low wages; my own wages being just 2 pounds per week. As the mugs were very large, we soon found that if we requested the canteen staff to fill them to the brim, we could pour a little from each mug, and thus gained two or three extra cups. As we only paid for the mugs filled up by the canteen staff, the operation netted us approximately six to eight pence per trip. Wealth indeed for poorly paid apprentices.

At the end of the day, the mugs were collected and taken for washing. Many of the men would lock their clean mug away but the charge hand, Ron Brown, refused to do this and placed his mug at the back of the bench. At this time, the heavy machines worked on a two shift system and from time to time, the evening machine shift workmen, would search for clean mugs to borrow for their own tea break. Ron Brown's mug was often taken for this purpose, much to his disgust as the apprentices refused to wash dirty cups in the morning. To prevent his mug being used for this purpose, Ron drilled a taper hole in the thick bottom of his china mug and manufactured a taper plug from stainless steel, which exactly sealed the aperture. The plug was kept in his pocket and solved the situation for some days until one of the evening shift re-drilled the mug making the aperture slightly larger. This was not discovered until the next day; when Ron lifted the tea filled mug from the apprentices delivery tray the plug fell through and the tea drained onto the floor.

My six months in the tool room passed quickly and happily; I was very fortunate that in this time we made several new prototypes, one of which was the Standard ABP safe, which later became one of the company mainstays in the commercial market. I also made a number of good friends amongst the trade apprentices, one of whom, Jeff Smith, became a lifelong friend.

The only negative feature of my time there, were the constant clashes with the tool room inspector, John Divine, a Scotsman, small in stature, who seemed to feel that his object in life was to make apprentices lives as difficult as possible. After he discovered that I was a rather better mathematician than he and was able to show him a number of solutions to class work he had been set at the local college, his attitude did thaw a little.

In addition to working a five-day week, apprentices were required to attend the local technical College in order to gain suitable engineering qualifications. We were allowed to attend college one-day per week, for which we were paid, and as many evenings as were required to follow through the course. As a student apprentice, I was required to follow engineering courses leading to the National and Higher National Certificates in mechanical engineering. Having obtained a good School Certificate in my fifth year at Grammar School, I was excused year one of the five-year course. It was certainly a hard slog attending for evening study after a full days work, as well as doing home work in whatever free time was left.

After the tool room I was sent to the Lock Works Machine Shop,where all the parts for Chubb locks were made as well as small turned parts for the light product works and the safe works. Almost all of the machines were operated by women, who seemed to tolerate the monotony of repetition work much better than men. Certainly, when I operated one of these machines for half a day, which I did occasionally, I became extremely bored. After the men in the tool room, these working ladies were a great shock, not only by their unprovoked comments to a young man but also by their conversations with each other. In these politically correct days, it would be considered as sexual harassment but then, it was taken as a necessary evil in one's education as an apprentice!

The machine setter for whom I worked was Billy Cox, a most interesting character, and a pleasure to work for. His great passion in life was gambling on both horse racing and greyhounds and he seemed to do very well in his gambling activities. In those days I suppose his pay would have been 40 to 50 pounds per week and he would often keep three or four unopened pay packets in his ‘cow gown’ pocket. When I enquired why he did not open these pay packets, he replied that he was able to provide his wife's housekeeping money and his own pocket money from his gambling winnings. It is amazing these days, to reflect that upwards of two or three hundred pounds was left overnight in his locker and to the best of my knowledge, he never had money stolen.

One of the ladies who operated the heaviest repetition lathe was a buxom blonde who called herself Lil. She was the women's Union Representative and fortunately for me, befriended me and instructed all her fellow workers to be careful what was said to me. As a result I had a far easier time during my six-month spell than many of my fellow apprentices, who generally disliked working in this environment.

The locksmith's benches were also located at the end of the machine shop and at that time, there was probably 50 or 60 locksmiths hand finishing and assembling all the Chubb locks produced. Only the lock apprentices, who served a seven-year apprenticeship, were allowed to work on the lock benches, but I was encouraged, when not otherwise busy, to watch the locksmiths and discuss any aspect of their work which I did not understand. Following my National Service however, as a special concession, I was allowed to spend some time on the lock benches, where I learned a great deal about combination locks, which was extremely useful in my later career.

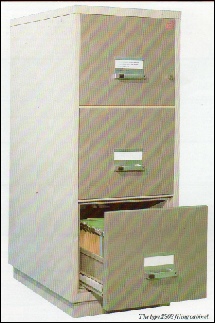

My next move was to the Light Product Works, where I was given the job as assistant to the foreman, Horace Ward. Although I did not learn any engineering skills during this period, I did see at first-hand, how Horace organised the factory to meet the production requirements and possibly more interestingly, the constant battle he had with a number of the drawing office staff, in obtaining sensible and accurate production drawings. One incident stands out clearly in my mind. The company had obtained a significant order from the Canadian government, for a secure version of the Chubb four drawer fire resisting filing cabinet.

This was for use in their overseas embassies and was to be fitted with a Sargeant and Greenleaf manipulation proof combination lock. The lock secured the second drawer down and the locking system needed to ensure that this second drawer could not be closed and locked if any of the other drawers were left slightly ajar. This was a counter to possible Russian espionage, which was rife at this period. The required system was totally dissimilar to that fitted on the standard unit. The solution provided by the designers, comprised dozens of small piece parts which all had to be assembled using screws. This was very time-consuming and did not produce a totally reliable locking system. After a considerable period spent trying to make the designed system more efficient and having discussed the problems on numerous occasions with the designer, without avail, Horace designed a very simple system himself, which he sketched on a piece of paper and presented to the drawing office. The system was immediately adopted and worked wonderfully well.

One other skill, I learned during this time was forgery. Horace was required to sign all replacement notes for consumable tools such as drills, grinding discs and files. His frequent absences from the shop floor during the saga of the Canadian government contract, led to delays and frustration among the shop floor workers requiring parts from the stores. I quickly learned how to copy his somewhat complex signature which caused him great amusement and from then on, I signed virtually all replacement tool notes on his behalf!

My next assignment was again in the light product works on the fire resisting filing cabinet section led by Walter Webb, another very patient and able apprentice instructor. On the section I worked with another apprentice, Brian Moore, whose father and uncle were welders in the factory. Brian himself went on to become a first-rate welder and here again, I developed a lifelong friendship.

My next assignment in the light product works was to the safe deposit section. At the time, this was one of the busiest sections in this factory as there was a great demand for safe deposit facilities throughout the world. Each installation was fully assembled on the shop floor before packing and shipment overseas where the majority of these installations were required. Again, I was fortunate in having a very good supervisor, Billy Stean. In addition to working on the specified sections, I was encouraged to take a keen interest in all the other products manufactured in this shop.

I then moved to the Safe Works; a very noisy shop, particularly on Mondays, when the heavy steel outer bodies of safes which had been bent on machinery, were set or corrected to the final shape by hand. This involved much heavy hammer work. As a result, almost all the safe makers were deaf, a situation which modern Health and Safety legislation would not tolerate. In later years, the Company issued ear defenders and ear plugs to all workers in noisy areas.

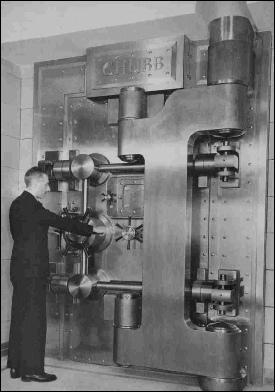

My placement was in the heavy door bay, where all vault doors were manufactured. The manufacture of the doors, their operating systems and particularly their hinging and compression systems, which made them water resisting, was very interesting. Unfortunately, on this occasion my supervisor, knowing I was not a trade apprentice, declined to allow me to do anything but the simplest jobs. His idea of keeping me employed was polishing the edges of stainless steel covered doors. After I had protested to him that I was learning very little about vault door mechanisms, he gave me jobs manufacturing special tools for use in his work. At least this was interesting although not quite what I felt I should be doing. I therefore spent as much time as possible examining the manufacture of heavy safes, night safe installations and many other products made in this shop. One of the fitters in the heavy door bay was Les Minshall, a very rough diamond, but extremely interesting as he carried out many overseas installations for the Company. I wish I had been fortunate enough to be placed with Les but at the time he already had an apprentice attached to him.

Towards the end of my time in the safe works, Mr Leonard Dunham visited the factory and during a tour, stopped to inquire whether my ambition was still to join the export department. On receiving an affirmative answer, he advised that he would make arrangements for me to spend the last two years of my apprenticeship in London, both with home and export sales, to complete my training. I was extremely excited at this news but rather worried as I knew it was very expensive to live in London. However, my mother made arrangements to lodge me with a friend of hers who lived in the northern suburbs. Much to my dismay, some weeks later I received a message from Mr Dunham advising that after further consideration, the board and particularly the Chairman Mr George Chubb, had decided that I should spend a further year at the factory. In retrospect, this was probably a wise decision since it meant I was able to continue at the local technical College and complete my studies.

My next period of training was in the drawing office, which was a most pleasant change after the factory as we didn’t need to report until 8.45 in the morning and finished work at 5pm. The shop floor hours were 8am to 5.45pm except on Tuesdays, when there was a late finish at 6pm.

I was not then nor ever have been, a good draughtsman, though I have always been able to sketch new designs, which can then be later turned into full working drawings by a professional draughtsman. In view of this, I was not particularly concerned by my lack of drafting ability, as I saw my future job in accurately describing the clients' requirements to the designers. I was not overly impressed however, with the abilities of some of the professional draughtsmen, who very often produced designs without any reference to, or input from, the men on the shop floor who had to translate the drawings into finished products.

It was a concern I expressed many times during my working career, believing that designers ought to go on the shop floor more frequently to see what problems their designs caused the fitters and how these designs could be altered.

My next period of training in the offices was in my opinion, a complete waste of time. The Company had a payment by results system for the shop floor and needed time study engineers to set the manufacturing rates for individual items. I was placed with a rate fixer, Joe Johnson, who although a very pleasant individual, had a somewhat cavalier attitude towards his work. He did at least allow me to make a number of job studies; I suppose the benefit I gained was learning to estimate quite accurately how long jobs would take to carry out which proved very useful in later years.

At this time, considerable efforts were being made to produce a new fire resistant compound for use in our fire resisting products. David Tate, the chief designer, was deeply engaged in this research and I was fortunate enough to be given the job, together with Ron Swift, the next senior apprentice, in producing models using new fire resisting media and testing these. As a result of this work, I developed a lifelong interest in the fire resisting product side of our business including, much later on, the very successful Data Protection Cabinets for computer media. I also developed a very close relationship with David Tate, which was extremely useful to me in my later career. Ron Swift, with the assistance of David Tate, became an extremely successful designer for the company and was deeply involved in the design of the excellent isolator system, used on all heavy safes and some vault doors, in later years.

Ron and I, instructed by Les Tinkler, the chief estimator and apprentice supervisor, designed a very simple night deposit system, based on the size 5 wall safe, for which we made the prototype. I later produced the working drawings for a product, which became very successful in the commercial market and was still being produced at the end of my career.

At the end of my fourth-year, I was again seen by Leonard Dunham and asked if I still wish to join the export department. Again, my mother made arrangements for me to lodge with her friend in north London but for the second time I was to be disappointed as Mr George Chubb decided that my sales training should be based at the local Birmingham branch.

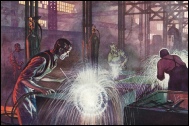

ABP(Anti-Blowpipe) Alloy being poured in the Foundry, watched by the Chairman, George Chubb(2nd from left)

ABP Safes in the Paint Shop

Range of Fire Resistant Cabinets pre WW2

Fire Resisting File from the range of units produced in the 1980s

1938 Treasury Strong Room Door - Weight 30 tons Total door thickness 34 inches - door slab 20 inches

Fitters in the Safe Works ‘Heavy Section’ assembling Vault Doors during the 1950s

At that time, the Birmingham Home Sales Office was located in Newhall Street and managed by an amiable but rather lazy individual, namely Frank Hall. His main efforts were directed towards the smooth running of a contract with the Kalamazoo Company, a Business Systems organisation who purchased special fire resisting cabinets from Chubb, and conducting a love affair with a divorced lady, which necessitated him spending a great deal of time away from the offices. There were three sales representatives; Tom Hansell and Geoff Stobbart were responsible for safes and fire resisting equipment and a lock representative. There were two secretaries and the engineer, Peter Dewey.

Of the representatives, Tom Hansell was quite the most selfish and offered me no training whatsoever. Geoff Stobbart however, was quite the opposite and gave me every encouragement even allowing me to go out with him whenever permitted by Frank Hall. My main task however, was to service the showroom and on several occasions I was able to make good sales of safes, locks and fire resisting equipment. The frequent absences of Frank was a benefit in that I really had to do what I felt was best in the absence of a manager. Unfortunately, the commission for any sales went directly to the salesman responsible for the area to which the equipment was delivered. Although I sold several pieces of equipment from which Hansell benefited, I received very little thanks. Fortunately, this did not go unnoticed by Frank Hall, who towards the end of my final year, paid me a bonus of 15 pounds, at that time a very handsome sum, which paid for a week's summer holiday for my family.

The most beneficial relationship I developed during my time at Birmingham was with the engineer Peter Dewey, who allowed me to help him in the workshop when I had little else to do. At that time, engineers were not provided with transport by the company and had to use public transport when they went out on jobs, unless one of the representatives would give them a lift. Quite soon, Frank Hall trusted me to cut keys, re-combinate locks and even carry out service work using my own transport, a small motorcycle, when Peter was out of the offices on service calls.

Geoff Stobbart, also gave me some very welcome field training in sales and after a time felt confident enough in my abilities to allow me to go out on his behalf to visit customers. I can still recall vividly, the first successful sales call I made, at the Bulmers cider factory in Hereford, where I successfully negotiated an order for a 9406 fire protection filing cabinet in competition with both Chatwood and Milner, who were our main rivals in the domestic market.

In September 1955, I completed of my five-year apprenticeship, during which time I had also gained National and Higher National certificates in mechanical engineering, with distinctions in two subjects and had twice won the Chubb prize for best results by an apprentice. Strangely enough, my distinctions were in subjects which had no relevance to my employment with Chubb but reflected a long time interest in steam and gas turbine engines. With National Service looming, deferment having been granted for the period of my apprenticeship, I followed advice from my gas turbines tutor and switched my option for service in the Army, to service in the Royal Air Force. This would enable me to gain experience on jet engines.

For the next four months, I continued at Birmingham branch awaiting my call up papers; I was finally inducted into the Royal Air Force on January 12th 1956, at the ripe old age of almost 23.

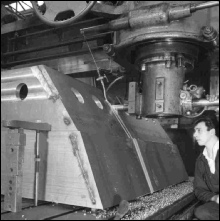

Drilling bolt holes in a Vault Door

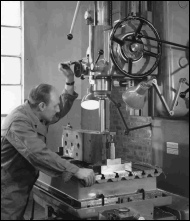

Drilling pivot holes in a hinge

Utmost accuracy is required at all stages in the manufacture of Vault Doors.

The pictures below illustrate two of the many precision operations.

Packed,loaded and off to the Docks

Chubb Lock & Safe Works in Wednesfield Road

Home | Previous Page | ToP | Next Page

| Chubb 1818-1990s |

| Chatwood-Milner |

| Chubb Family |

| Early Sales/Offices/ChubbGroup/1980s & on |

| The Detector Mechanism |

| Photographs |

| Chubb Money Boxes |

| The Aubin Trophy |

| Lock Number 696 |

| Williams acqusition |

| Arthur Briant |

| Ibbs - Export is Fun |

| Peter Gunn |

| Back to Work |

| First Steps |

| My Export Career begins |

| The Happy Years |

| Export Manager |

| Back to The Midlands |

| Back to The Midlands - part 2 |

| Australia |

| The Midlands - again! |

| The Final Years |

| Conclusions |

| Slingsby Dart T51 Sailplane |

| Latest News |