The Chubb Archive is part of The History of Locks Museum Resources

Contact our curator for more information

© 2004 - 2016

Your one-stop resource for dating & information on vintage and antique Chubb Locks, Safes & Security Equipment

Export is Fun

Mr. D.R.E. Ibbs’ personal memories of his 41 years with Chubb

Export Manager

My major problem as manager was the lack of experience in my staff. Apart from Derek Whitehead, whom I immediately promoted to assistant manager, all the sales staff were very young and recently arrived from Home Sales. I was able to embark on training, which had long been a bee in my bonnet and called on the expertise of works personnel to teach the reading of drawings, which I felt to be imperative for salespeople who would be talking to architects. The other innovation I brought in was based on my own early experience, when I had been despatched on my first overseas trip, without any basic briefing.

My solution was to accompany the representatives on their first trip, to the initial country on their itinerary. In this way, I felt they would quickly overcome the nervousness they were bound to feel and also get some idea of the way I felt overseas agents should be handled. The first of my men to receive this on the job training was Stuart Holliday, recruited from home sales after a successful stint, mainly in Ireland. I don’t think Stuart will ever forget that first week. He was so anxious to have answers to every possible query, technical or otherwise, that he stuffed his briefcase with drawings, costs, literature etc., so that it must have weighed 30 or 40 pounds. I carefully ensured that he carried it himself during our first week's work in Portugal. It must have been beneficial however, as Stuart remained in export for more than 29 years and has been extremely successful.

My next trip with a trainee, some months later, was with Colin Lovett and produced one of the most puzzling and somewhat sinister occurrences to befall me during my export career. I had elected to accompany him to Greece, by now an important Chubb market, where I knew that Arthur Hill, the local agent, would help me to introduce my trainee to the rigours of export life. We were booked to stay at the King George V hotel in Ammonia square. On the morning of our departure, literally minutes before we left the airport, Arthur telephoned and advised that due to overbooking, we had been transferred to the sister hotel, also in the square, the Grande Bretagne. After a pleasant flight to Athens on the Comet, we checked into our hotel and immediately set off with Arthur, to his home in the suburbs where we were entertained to dinner. We took our leave of the Hills at about 11 p.m., travelling back to the city centre by train and finally collected our keys from the night porter at about midnight. Checking out the key requests against the register, he told us that a lady had been inquiring for Mr Ibbs. We laughed and jested that my luck had obviously changed, before retiring to our rooms.

About 2am I was awakened by the telephone and on answering, greeted as ‘Mr David’ by a soft female voice, who went on to tell me that her name was Sandy and that we were acquainted. She further advised that she had something urgent to tell me, and needed to see me at the hotel immediately. I assured her she was mistaken and that I knew no one called Sandy and inquired how she felt we were acquainted. She advised that we had met the previous year in Cairo and to my consternation, went on to display considerable knowledge of my most recent trip to Cairo. She went as far as to suggest that we had an affair there and she was most anxious to continue our close acquaintance immediately. Thoroughly alarmed at the conversation, which was a total fabrication, but also deeply curious, I let her continue the conversation, during which she explained she was less than five minutes away from the hotel. As she was talking I became aware of a clock ticking loudly in the background; subsequently, this time piece assumed some significance.

I rang off but lay sleepless, pondering the meaning of this curious call. At breakfast, I mentioned the telephone call to Lovett and told him I felt it was a stupid practical joke by one of the Hill brothers, who had a reputation for that sort of thing. Having lost a night's sleep, as he drove us to his office, I told Arthur Hill I was not amused. Directly we reached the office he went off to find his brothers. They all came back to his office and said the joke was none of their doing, further pointing out they had no knowledge of my travel movements the previous year. I then decided to contact Karl Striebel, who, having been promoted to NCR’s Director for the Middle East, had moved from Beirut to Athens. He was very surprised to see me and vehemently denied involvement. This rang true as I’d not intended to visit him on this trip. The matter was growing more and more curious and over lunch we had a lengthy discussion about it with all the Hill brothers. The only clues were Sandy’s claim she was calling from premises within five minutes of the Hotel and, unless my ears were playing tricks, there was a clock with a very loud tick-tock close to the telephone. With this slender amount of information, Archie Hill said he would inquire among acquaintances to try to discover location - and discover it he did.

Two days later he gave me the name and address of a cheap hotel, just off the opposite side of the square. After completion of business that evening, Lovett and I went there and found the Greek proprietors spoke little English but after some mime, I used the name Sandy and immediately recognition dawned in the eyes of mine hostess. With a burst of Greek, she despatched her husband and made us aware he had been sent to bring Sandy. We quickly moved out of the foyer and as I was certain she wouldn’t know which of us was ‘Mr David’, told Lovett to keep quiet. A few minutes later, a young pleasant looking Greek prostitute approached and said "Hi, I’m Sandy". She stood looking from Lovett to me and back again as we said nothing. Finally, I said "you rang our hotel last night asking for Mr David and saying that you knew him well”.

She agreed this was so. "And which of us is Mr David" I inquired. Looking confused she eventually said she didn’t know. After some heated discussion she agreed she had never met either of us in Cairo or Athens. Someone she did not know had offered her payment and briefed her on what to say when she spoke to me. I was now thoroughly alarmed, as I was satisfied that it was not a jape by either Striebel or the Hills -- but if not, whom? It was certainly someone who knew of my movements of the previous year .

My alarm was made all the greater, when I recalled that some years previously, a British businessman, Greville Wynne, had been arrested for spying, by the Russians, and after his release in exchange for Russian spy, the story had been made public that he’d been blackmailed by British Intelligence to act as a courier during his business trips behind the Iron Curtain. I was aware that I had met a number of British ‘spooks’ during my travels in the Middle East - could M.I.6 have been behind this episode in Athens? It seemed hardly likely as Bill Randall did not allow us to travel behind the Iron Curtain but I was certainly constantly working in some fairly hot spots around the world.

My alarm was made all the greater, when I recalled that some years previously, a British businessman, Greville Wynne, had been arrested for spying, by the Russians, and after his release in exchange for Russian spy, the story had been made public that he’d been blackmailed by British Intelligence to act as a courier during his business trips behind the Iron Curtain. I was aware that I had met a number of British ‘spooks’ during my travels in the Middle East - could M.I.6 have been behind this episode in Athens? It seemed hardly likely as Bill Randall did not allow us to travel behind the Iron Curtain but I was certainly constantly working in some fairly hot spots around the world.

On returning home, I immediately rang Reg Pilgrim at his home and later that evening recounted the strange events in full. He heard me out, accepting my assurances that I had never met Sandy previously, either in Cairo or elsewhere. The next morning, he spoke with Peter Hamilton, Chubb’s in-house security adviser - and, so it was said, an ex-spook. I recounted my story to Peter and after I had finished he stated briskly that he would telephone some "friends" and that I should forget the incident. I never heard any more and to this day, have no satisfactory explanation for this very worrying affair. I’ve no doubt it was a blackmail attempt but by whom and for what ultimate purpose I’ve no idea. I do know someone had spent a lot of time and effort, checking on my past movements and paid money in setting up the incident.

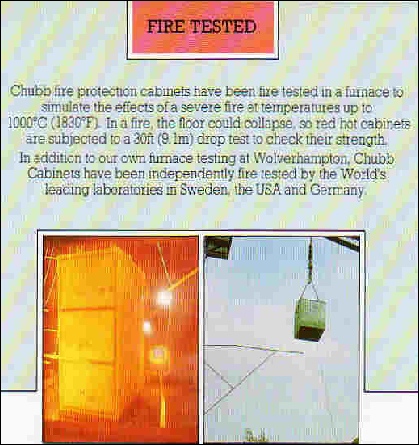

I continued a tradition that Bill Bannochie had instigated, this being an annual training course in England, for the salesmen of overseas agents. In the early days it had been something of a junket for the attendees but gradually, we increased the technical content and reduce the hangovers. Undoubtedly, it had a beneficial effect on our overseas trade and also introduced the Chubb export staff to overseas sales staff from territories they had not visited. A welcome side effect was the start of some lifelong friendships. On these training courses I was helped greatly by Harry Eary, a very experienced Home Sales Manager, who introduced home sales staff to the joys of selling. In the early years, Harry and I carried out much of the training, aided as necessary by expert staff from Wolverhampton, where the courses were held, and the research staff who conducted the practical demonstrations of fire testing, oxy acetylene cutting and other methods of attack.

One of the more amusing incidents during these courses involved the late Ron Brown, the explosive and firearms expert in the research department. At the time, the factory had an explosives bunker on site and I had obtained permission to demonstrate how simple it was to blow open old-fashioned safes with a small explosive charge. To this end I’d located an old Milner safe from a stock of units we had removed when installing new equipment.

On arrival at the explosives bunker with our guests, I was slightly concerned to find this unit had been replaced by a Hobbs Hart double door safe of much heavier construction. Apparently, Ron had selected a heavier unit as he felt the Milner unit was unworthy of his talents. I asked him if he had opened the safe to check the door mechanism. He cheerfully assured me that although he hadn’t done this, it would not cause him a problem. Ron commenced his lecture on the method he would use and stressed the very small amount explosive required to dislodge the locks and allow the door to be opened. His salty language and turn of phrase always went down well with visitors, who felt that they were really being taken into the confidence of an expert in the dark arts of safe cracking. Finally, he loaded the 15 grams of explosive into the keyhole, using a condom to hold it in place. All of us having retired to a safe distance, Ron detonated the charge and we returned to see the results of his handiwork. Apart from a few flakes of rust and paint which had been dislodged from the door of the unit, the safe remained obstinately locked. Ron expressed surprise and advised that he would double the size of the charge, which would undoubtedly do the trick - again nothing! By this time the audience were becoming restive so I whispered to Ron that I needed him to guarantee success on the third attempt. Unfortunately, that was no more successful than the first had been. Ron looked very embarrassed, muttering his apologies to Harry and I; at this point we took the group back to the lecture room for the next subject.

Ron came to see me the next morning and explained what had occurred. He grinned and told me that having used a huge charge yesterday evening, the top of the safe had peeled back like the lid of an old sardine can. He was then able to see the safe was an old ‘hook-bolt’ banker's unit and, having been left outside for some years, the hook-bolts had corroded in the fixing slots. Although, as he’d forecast, the first explosive charge had detached the locks, nothing would have allowed the doors to open - so bad was the corrosion. Later that day Ron opened the original Milner safe (which I had checked) using a very small charge.

Ron always remembered the incident and over the years, we laughed about it on many occasions. My abiding memory is the wording of his apology to Harry and I - "Oh I am unhappy" - just one of his quaint turns of phrase.

Gradually, the department became an excellent cohesive unit and the results certainly showed this. Much to my pleasure, the turnover improved dramatically from the Johnston years and I felt that this was a complete vindication of my training and management methods - particularly after the previous administration. In the words of the salesmen who worked for some time under Johnny, "all he ever did was to hit us with the thick end of a memo".

During this period, I lost the services of Albert Newman, my office manager. He made the mistake of telling me he’d obtained another job and would take it up, unless I improved on the financial package which he indicated he was to receive. He was flabbergasted when I asked for his resignation and demanded to see the company secretary, Don Potter, to see whether he could blackmail him into the substantial increase he had asked for. I was very pleased when Potter confirmed my decision. It left my office administration woefully weak and I suffered for it for some time. Thankfully, I was fortunate enough to obtain the services of Bob Sherwood - Miller, who ultimately settled into the job very well, creating a happy administrative backup, as well as a good rapport with the factory where he had previously been employed.

Some time later, Newman applied for his old job back again when the post he’d moved to turned out to be less than satisfactory. I was relieved when my decision not to re-employ him was supported by my managing director. This was due in part I understand, to anxiety expressed by the security service, regarding his friendship with a Russian embassy official, whose recall was demanded by the foreign office.

In the late 1960s the EEC was expanding and I was instructed by the board to increase exports in the area. We already had a sizeable turnover with the EFTA countries but our business in the EEC was minimal and at very poor margins. It was mainly in France and Italy, the emphasis being on the Cash Dispenser, Chubb being one of the main manufacturers of this very new innovation. Unfortunately, we could not persuade the French or Italians to invest in the service backup required for these high tech machines and consequently, we had endless trouble and arguments with the agents as it usually entailed us in dispatching British engineers at no charge. All in all, the business must have been a dead loss to the company. It was against this background the order came via the sales director Dick Chapman, to increase European business.

I argued for my percentage profit contribution to be reduced to take into account of the lower margins obtained. Having this argument rejected, I decided to use sales people part-time only on Europe, in order to obtain more profitable business from our traditional markets. I decided to concentrate on selling fire protection units, in which we had a very good business with the EFTA countries, particularly Switzerland. Finally, the salesman for Germany, Mike Sayer, appeared to crack the problem and following an exhibition, a German office equipment company expressed keen interest in distributing Chubb Fire protection units, particularly filing cabinets. Mike and I set off hot foot for Germany where we had a very positive meeting with the directors of the German firm, which resulted in an agreement to supply them with an initial order of 30 units by lorry. As the price negotiated was substantially higher than that at which we supplied similar equipment to the French, although still lower than we obtained outside Europe, I felt we had done an excellent job.

I argued for my percentage profit contribution to be reduced to take into account of the lower margins obtained. Having this argument rejected, I decided to use sales people part-time only on Europe, in order to obtain more profitable business from our traditional markets. I decided to concentrate on selling fire protection units, in which we had a very good business with the EFTA countries, particularly Switzerland. Finally, the salesman for Germany, Mike Sayer, appeared to crack the problem and following an exhibition, a German office equipment company expressed keen interest in distributing Chubb Fire protection units, particularly filing cabinets. Mike and I set off hot foot for Germany where we had a very positive meeting with the directors of the German firm, which resulted in an agreement to supply them with an initial order of 30 units by lorry. As the price negotiated was substantially higher than that at which we supplied similar equipment to the French, although still lower than we obtained outside Europe, I felt we had done an excellent job.

On return I immediately saw Dick Chapman to report our success and advise the terms and prices agreed. To my amazement, instead of congratulations he told me that he would not accept the prices I had agreed and I must telephone Germany to advise the price had to be increased. I was furious, pointing out the prices negotiated were higher than those given to the French, which Dick Chapman himself had agreed! After an angry discussion, he conceded the first load could go at the prices quoted but thereafter, I had to tell them that we would charge higher prices. In high dudgeon, I refused and told Chapman if that was how he felt about my negotiating skills, he could go and tell the Germans himself. In future, I would concentrate on the more profitable areas. Naturally, the German company told him what he could do with these higher prices and we lost a golden opportunity.

I never again dealt with the EEC and quite why Chapman responded in the way he did, I never found out. In later years I had many arguments with other employees about Dick's selling abilities. Personally, I always found him to be a very coarse man who seldom made good, well thought out decisions; he seemed to regard his position as a golden opportunity to live well on expenses but rarely delivered the results to justify those expenses. In this he was not alone, as I was to discover during my later overseas posting.

At this time, we seemed plagued by poor senior management which made life very difficult. Harry Thorpe, the former Chatwood Milner Managing Director, was promoted to oversee Chubb and as Export Manager, I needed to deal with him quite frequently. He had an explosive temper and if he felt something needed to be investigated, he did not seem to care how much time he wasted in minutely examining the details. On one such occasion, he received a complaint from South Africa about incorrect invoicing. As a result, I and many members of the department, spent the whole of one day looking into the matter. We found the problem related to a group of four cases being incorrectly numbered in the packing shop, which resulted in the shipping clerk, working only from the paper records, incorrectly describing and pricing the units in the cases. That the overall costing was correct and the error was a genuine slip by a case marker, simply did not matter to Thorpe and by the end of the day, many hours had been wasted, to no avail.

At this time, we seemed plagued by poor senior management which made life very difficult. Harry Thorpe, the former Chatwood Milner Managing Director, was promoted to oversee Chubb and as Export Manager, I needed to deal with him quite frequently. He had an explosive temper and if he felt something needed to be investigated, he did not seem to care how much time he wasted in minutely examining the details. On one such occasion, he received a complaint from South Africa about incorrect invoicing. As a result, I and many members of the department, spent the whole of one day looking into the matter. We found the problem related to a group of four cases being incorrectly numbered in the packing shop, which resulted in the shipping clerk, working only from the paper records, incorrectly describing and pricing the units in the cases. That the overall costing was correct and the error was a genuine slip by a case marker, simply did not matter to Thorpe and by the end of the day, many hours had been wasted, to no avail.

Thorpe's relaxation was playing in a band and this brought about a curious and unpleasant situation. The company decided that it would celebrate the 150th anniversary of founding in 1818, by holding a rather grand banquet at the Cutler's Hall in the city of London. All senior managers were required to attend and entertain a cross-section of the company's clients. Dinner jackets were the order of the evening and as I did not own the formal attire, I hired my kit, as did many of the other managers.The evening passed off extremely well. Nothing further was said until the end of the month when our expenses were submitted, including in my case, the hire charges for the dinner suit. My immediate manager was Reg Pilgrim and later that day he advised me that on instructions from Thorpe, these hire charges had been struck off my expenses, on the basis that as he, Thorpe, had a dinner suit (presumably to play in the band!), it was incumbent on all other managers to own a suit. To be fair, Reg protested the matter but Thorpe was adamant. Some days later, the matter came to the attention of Bill Randall, by now the Group MD, and Thorpe was quietly overruled. Such was the quality of some of our managers!

This problem of poor senior management seemed to stem from the very rapid increase in the size of the Chubb Group, now incorporating Union, Chatwood Milner, Burgot Alarms, Read and Campbell, and Pyrene, to mention but a few. Chubb managers were moved from the Lock and Safe Company, to prop up the weak management in many of the new companies and their managers were brought into Chubb. It was the classic thinking that if we dilute our good managers with their weaker managers, the poor ones will get better - quite at odds with the real-life situation where a rotten apple in the barrel will quickly spoil the others. That both Chapman and Thorpe were quickly moved, mattered little - the rot had begun.

I was involved in many exciting expeditions during this period. For many years, the Scandinavians had purchased Chubb strongroom doors, albeit after exhaustive testing. There was great excitement therefore, when there were two or three quite novel burglary attacks in Sweden, in which acid was sprayed into the key locks on strongroom doors, dissolving the brass locks and allowing entry. The Swedes insisted that before they would purchase anymore vault doors, manufacturers must come up with an acid resisting lock. One obvious answer was to fit combination locks but, as requested, we experimented and produced a key lock at which would resist an acid attack. Of course, the Swedes had to check this fact themselves. On this occasion I accompanied Trevor Braybrook, our Works Director, to Scandinavia. The new lock passed the test with flying colours and our strongroom door business resumed.

We were also supplying considerable numbers of fire resisting filing cabinets to Switzerland and initially, the Swiss accepted our fire test certificates. They then decided they wished to test the cabinets themselves and so I accompanied Stanley Radford, the Research Director, to Zurich, where we tested a three drawer filing cabinet, which easily passed the test. The Swiss testing authorities were amazed since all competitive units had failed the test. As a result, our business increased and led to the German inquiry, which I mentioned earlier.

Time passed very quickly as we were extremely busy; some other notable contracts being the huge Central Bank of Kuwait, admirably handled by Derek Whitehead and a large contracts for Cash Dispenses in Brazil, an area dealt with by the very able Stephen Phillips. Steve would be the first to admit that his technical ability was fairly rudimentary but as a salesman he had few equals and I still rate him as one of the best. Following his tremendous success with cash dispensers in Brazil, Steve felt that his future lay with the new cash dispenser company run by Gilbert Uwins and to my great regret, he left export department. Sometime later, one of the CDU sales managers, Hutton-Penman, recommended that Steve was totally unsuited to selling cash dispensers and he was transferred to CSI (Chubb Security Installations). I still feel this was one of the more classic errors by Hutton-Penman, who rated his own abilities rather more highly than did his peers; after all, to this day, Steve was responsible for the sale of more cash dispensers than anyone else within the Chubb group.

1970 proved to be a hectic year. Labour troubles in the country were creating high inflation and the salaries of the Home Sales staff, who were paid commission on sales, advanced rapidly. My own sales people, who in my opinion, were the equal or better than any home salesmen, weren’t paid anything like the home salaries. I tried in vain to win increases for them but the company had set its face against any reasonable increase. Sad to say, this was one of a few times that I fell out with my boss, Reg Pilgrim.

About this time my last trainee, Roger Cloke, joined the department. I was not keen to have him but he was wished on me and I suppose in retrospect, he had already been marked for a likely high flyer. At the time I assumed it was because he was married to one of Leonard Dunham's daughters and there are still those who maintain this was behind his rapid advancement in the Company. My training trip with him was to Spain, where we’d received news of a new Central Bank to be built. I did not expect we would be successful as we had never previously done major business in Spain. However, we were well received and it did not seem to be a hopeless cause. Under guidance, Cloke worked on the project which was quite a sizeable scheme. Before it went too far however, I was transferred from the department and promoted to a Home Sales position, so apart from the initial work, I can claim very little input. That Cloke went on to secure the project against fierce and somewhat underhand competition from American safe makers, is to his great credit and eventually earned him the National Westminster Bank's award of "Young Exporter of the Year”. I had unsuccessfully contested some years before although in fairness it must be said that in my case the entry was entirely my own work whereas Roger had considerable help from a PR Company.

The ill-fated postal strike began and knowing full well my business depended on the mail - few companies having telex machines at that time - I made immediate arrangements to have all my mail routed through our Belgian Group Company. I would collect and despatch my outbound mail, once a week. To this end, one of the clerks was sent on the BAF car ferry service from Southend to Belgium and back, in a day. I advised Reg Pilgrim of my plans and received his congratulations for initiative. To my amazement, no other company within the group had made any contingency plans and so it was that all group mail came to the export department for onward transmission. From once per week, I was forced to increase the trips to three per week due to the sheer volume of mail. The clerks, who normally did not go abroad, thought it was a great perk and were rather sorry when the strike eventually ended.

The ill-fated postal strike began and knowing full well my business depended on the mail - few companies having telex machines at that time - I made immediate arrangements to have all my mail routed through our Belgian Group Company. I would collect and despatch my outbound mail, once a week. To this end, one of the clerks was sent on the BAF car ferry service from Southend to Belgium and back, in a day. I advised Reg Pilgrim of my plans and received his congratulations for initiative. To my amazement, no other company within the group had made any contingency plans and so it was that all group mail came to the export department for onward transmission. From once per week, I was forced to increase the trips to three per week due to the sheer volume of mail. The clerks, who normally did not go abroad, thought it was a great perk and were rather sorry when the strike eventually ended.

This postal arrangement had a rather unexpected result. For years past, ever since the Chatwood Milner Company operated as an independent within the Group, Chubb managers had complained that CM were undercutting prices, something that was officially forbidden and subject to tight controls by group. Bob Palmer having made such complaints, had been instructed to visit Chatwood Milner, where Harry Thorpe and Don Fairclough, the Managing Director and Export Manager, 'proved' to him they were abiding by the rules. However, the problem had festered on and I certainly believed that they were undercutting.

The volume of mail we were dispatching caused the Belgian Post Office to insist that all letters for a single destination country, were presented together. It was therefore necessary for my clerks to open the group enclosure envelopes and sort the mail into bundles for each country. This caused considerable extra work when we were already busy with our own export work. One day, I heard Bob Sherwood-Miller utter an expletive and the next moment he rushed in to advise me he’d accidentally opened what he thought to be an enclosure envelope. It turned out to be a Chatwood Milner quotation for a job in Kuwait. It so happened that I had just finalized the competing Chubb quote. I glanced down it to see what they were offering, which was similar to my own quoted items. To my amazement, their prices were way below my own, even though they had included a percentage for the agent, which mine did not. Although quoted on the C & F basis, the items did not seem to allow for freight or packing. I pondered on this as to whether omitting freight and packing costs might be a genuine mistake. Not satisfied however, I instructed Bob that he was to re-envelope the quote and dispatch it. Additionally, he was to obtain a supply of CM envelopes and all their future mail was to be opened so that I could look at the quotes. The revelations were staggering; far from being an error, virtually all CM quotes broke the rules and I built up a significant case dossier.

When the strike ended I went to Reg Pilgrim and told him that following my many complaints about Chatwood Milner pricing, which could never be resolved, I now had proof that they were continually breaking the rules. He listened to my story but did not comment on my methods. A few days later, he sent for me and inquired whether I would be prepared to talk to George Lemon, the group director with immediate responsibility for both Chubb and Chatwood. To say I felt worried is an understatement; I had known George Lemon since my apprentice days and found him to be a peppery little gentleman who was punctilious in respect of good manners and the correct way of doing things. What would he think of my underhand method of reading Chatwood Milner mail? It was with a heavy heart that I went into his office and told him how I had obtained proof that Chatwood Milner were deliberately and continually flouting the group rules on competition. He smiled and very courteously asked me if I was absolutely sure, to which I replied that I could quote chapter and verse. He thanked me and without inquiring how I had obtained the information, sent me on my way.

Some months later, the security companies were reorganised by amalgamation and the separate existence of Chatwood Milner came to an end. Henceforth, we would all be Chubb Lock and Safe Company Ltd. In this amalgamation, I was moved from Export to become a Regional Manager in the Midlands. Shortly after the amalgamation, Mr Lemon paid a visit to my headquarters to see how we were settling in. Privately, he explained to me that the board had known for some time that there was a problem with Chatwood Milner sales margins but the matter was so cleverly covered that he could not obtain proof of where the problem lay. My report had been the final straw and from that time on he was determined to recommend the amalgamation took place.

In March 1971, I along with several other senior managers were advised of the amalgamation and offered posts, the salary for mine being so much in excess of my export manager's remuneration, that I simply could not refuse. So it was that in April 1971, I left export to become the manager, Midlands and Southwest. In broad terms, this area extended from Humberside to Aberystwyth and Poole to Land's End, with existing branch offices in Birmingham and Bristol. Everything that occurred in the region was my responsibility, within the framework of the Lock and Safe Company.

Wynne (2nd from right) on trial in Moscow

BAF (ATL.98) Carvair

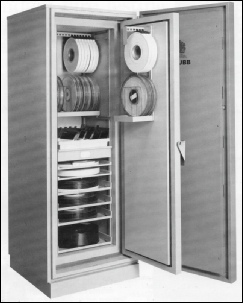

Size 2 Media Cabinet

Chubb Group Senior Managers at the Banquet celebrating the 150th anniversary of the founding of the Company.

(Mr. D.R.E.Ibbs is 5th from the left)

Home | Previous Page | ToP | Next Page

| Chubb 1818-1990s |

| Chatwood-Milner |

| Chubb Family |

| Early Sales/Offices/ChubbGroup/1980s & on |

| The Detector Mechanism |

| Photographs |

| Chubb Money Boxes |

| The Aubin Trophy |

| Lock Number 696 |

| Williams acqusition |

| Arthur Briant |

| Ibbs - Export is Fun |

| Peter Gunn |

| Back to Work |

| First Steps |

| My Export Career begins |

| The Happy Years |

| Export Manager |

| Back to The Midlands |

| Back to The Midlands - part 2 |

| Australia |

| The Midlands - again! |

| The Final Years |

| Conclusions |

| Slingsby Dart T51 Sailplane |

| Latest News |